This fall, the U.S. Department of State launched the Global Music Diplomacy Initiative to elevate music as a diplomatic tool to promote peace and exchange of ideas. In partnership with the music industry, the initiative includes a music mentorship program to bring artists from around the world to the U.S. for networking and training; a fellowship for scholars researching the intersection of arts and science; and using music as an English language learning tool around the globe.

So, what’s the State Department doing in the music business? Actually, the State Department has a long music diplomacy history, and an expert on this is Carol A. Hess, a musicologist and Distinguished Professor of Music in the College of Letters and Science at UC Davis.

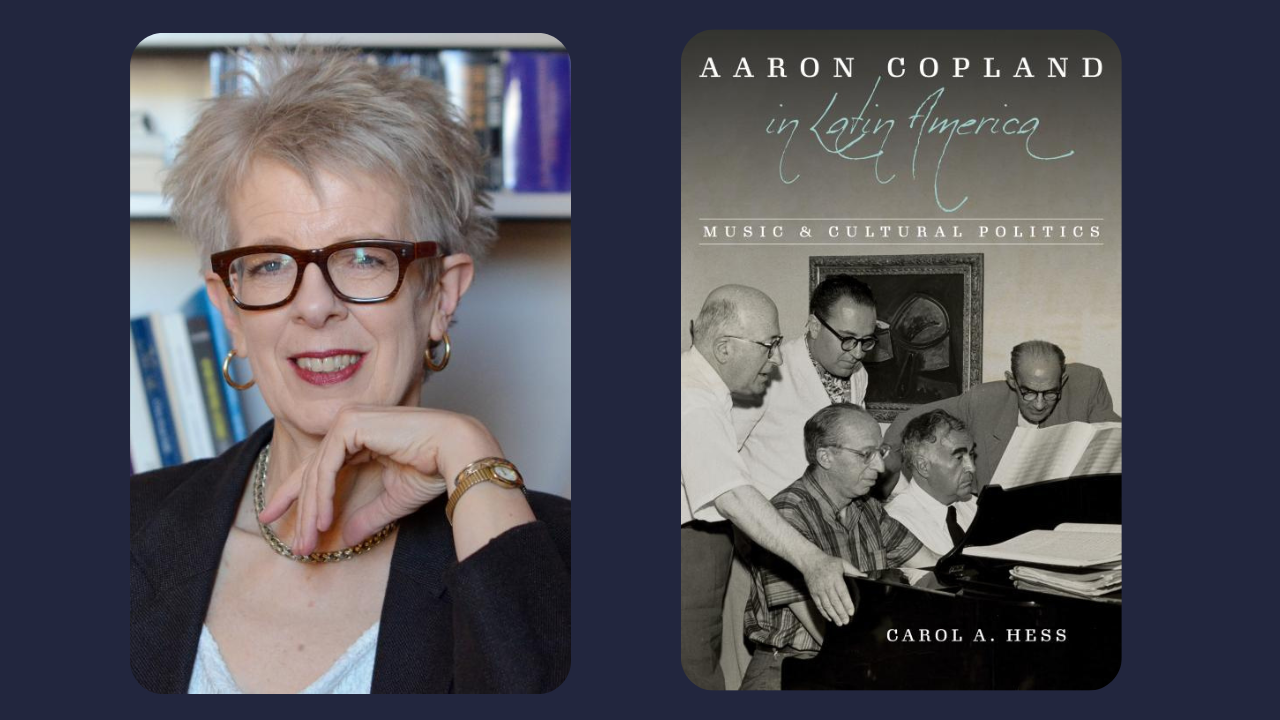

Hess has written two books on the U.S. government’s cultural and mostly musical outreach — the most recent Aaron Copland in Latin America: Music and Cultural Politics, published in February, and the 2013 book Representing the Good Neighbor: Music, Difference, and the Pan American Dream. Hess herself has been the beneficiary of cultural diplomacy programs in the form of two Fulbright Fellowships to teach in Spain and Argentina; those fellowships sparked her interest in the State Department programs.

When Hess — who in 1994 became the first person to earn a doctorate in musicology at UC Davis — entered the field, scholars were paying scant attention to Latin American classical music and almost none to music of the 19th and 20th centuries in the region, let alone cultural diplomacy in Latin America.

“In the 1990s, several musicologists began working on the special challenges involved with music and cultural diplomacy,” said Hess, who returned to the UC Davis Department of Music as a professor in 2012. “Most of these scholars, however, worked on the East-West divide of the Cold War. I realized that the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking world wasn’t getting much attention, so I decided to plunge into that.”

Building bridges, championing Latin American music

Copland is best known for his accessible compositions, often connected to celebratory narratives and vernacular music of the United States; the title of his Fanfare for the Common Man encapsulates his musical philosophy. Among his other popular works are the ballets Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid and Rodeo.

Despite a plethora of research on Copland, no scholar had ever explored his cultural diplomacy in Latin America. In Aaron Copland in Latin America, Hess documents Copland’s four State Department Latin American trips, which took place between 1943 and 1963. He conducted concerts (often programming his own music), gave talks and interviews, and sometimes traveled to rural areas with messages of cultural connectivity. Copland’s Latin American travels drew widespread attention in the media. He was a tireless promotor of the State Department programs, giving talks and writing about them for mainstream publications. Copland’s tours were so significant that they are mentioned prominently in the State Department’s recent announcement of the new music diplomacy initiative, along with tours by Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington and others starting in the 1950s.

“It’s one thing to say Copland was a cultural diplomat, but when we actually become aware of what he did on a daily basis, it’s quite impressive,” Hess said. “Other scholars have worked on cultural diplomacy in broad geopolitical terms — they’ve done essential work — but I wanted to address these big themes while also taking the reader behind the scenes a bit. How many meetings with composers, radio broadcasts, press interviews or embassy receptions might be on his agenda? This angle of cultural diplomacy — the sheer amount of work involved and how it fits into the bigger picture — isn’t often explored.”

One of Copland’s most important achievements was drawing attention to Latin American composers.

“Copland’s Latin American colleagues resented being typecast as purveyors of cheery, folkloric, maracas-and-drums works that invite U.S. listeners to a ‘south of the border fiesta,’” said Hess, who has written extensively about the music of Latin America and Spain, including books about composers Manual de Falla and Enrique Granados and dozens of scholarly articles.

Several Latin American composers did embrace a folkloric style, but others pushed the boundaries with avant-garde techniques. Having come late to the avant-garde himself, Copland didn’t initially support the latter group’s efforts, but eventually advocated for their music.

Like Copland, Hess is a champion of Latin American music with her students at UC Davis and many others through her 2018 textbook Experiencing Latin American Music, winner of the American Musicological Society’s Teaching Award.

“Many people worldwide know Latin American popular music but have no clue that Latin American classical music exists,” Hess said. “Students are usually intrigued when I inform them how pervasively Latin American classical music has been ignored.”

Cultural diplomacy cuts across political divides

The period covered in the Copland book spans World War II and the early Cold War, a time of shifting priorities in U.S.-Latin America relations, already tarnished by a long history of U.S. interventionism. Cultural diplomacy programs with Latin America were part of the fight against European fascism before and during World War II, thanks to former President Franklin Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor policy. In the Cold War, when communism was seen as the great threat, the United States resumed interventionism or supported anticommunist dictators in Latin America. Many Latin Americans concluded that the Good Neighbor policy had been insincere.

“Copland did not have an easy assignment,” Hess said. “Yet he spoke glowingly about the State Department and its cultural diplomacy programs.”

The early Cold War wasn’t a great time to do that.

In the 1950s, the State Department came under intense scrutiny by U.S. Sen. Joseph McCarthy and others, who alleged communist infiltration. Because of his leftist political activities during the 1930s, along with his enthusiasm for the State Department, Copland was questioned by McCarthy and investigated by the FBI.

Overall, State Department arts programs have had wide-ranging support among those of various political stripes. The sponsor of what would become the State Department’s Fulbright Scholarship and Fellowship program was U.S. Rep. J. William Fulbright, a Democrat from Arkansas with a mixed record on segregation but an opponent of McCarthy’s communist witch hunt.

Republican multibillionaire Nelson Rockefeller, who eventually served as governor of New York, assistant secretary of state and vice president, was appointed by the Democratic Roosevelt administration as coordinator of Inter-American Affairs in which cultural diplomacy was a major component.

This across-the-aisle support continues, even in today’s rancorous and sharply divided U.S. Congress.

The State Department’s new Global Music Diplomacy Initiative was made possible by the PEACE Through Music Diplomacy Act sponsored by U.S. Rep. Michael McCaul, a Texas Republican, and U.S. senators Thom Tillis, a North Carolina Republican, and Patrick Leahy, a Vermont Democrat.

“It’s interesting to see the range of politicians who support these programs,” Hess said.

U.S. cultural diplomacy initiatives have been criticized as “art washing” propaganda to promote U.S. political and economic interests, and in the case of tours by jazz giants in the 1950s, an attempt to show that the United States wasn’t a racist nation. Hess is well aware of such criticisms, and acknowledges hypocrisy in cultural diplomacy, such as proclaiming solidarity with Latin America while supporting repressive regimes.

“Still, I get irritated by those who say the whole thing is just an imperialist ploy,” Hess said. “Yes, imperialism guided many unfortunate policy decisions. But it’s important to remember that in the cultural realm, affective bonds were forged by individuals — by people like Copland. Copland treated the composers he met with respect and he remained an advocate and a friend to many for years after the tours ended. These benefits of cultural diplomacy can’t be measured in spreadsheets or cost-benefit analyses. Yet they run deep and, in Copland’s case, are fondly remembered today.”