The UC Davis Global Migration Center provides a uniquely comprehensive understanding of migration's profound impact on societies worldwide

Luis left his home in Guatemala to escape the criminal gangs that were extorting him repeatedly with a threat of violence. He left behind his family, his culture and his very identity for a chance to live the American Dream.

Instead, Luis made the dangerous journey north only to be confronted again with extortion but this time by authorities he expected to protect him. Then he discovered a tumor in his throat. His fortunes changed only when he found support from a non-profit NGO in Mexico that told him to go to a local hospital for treatment.

“I did not want to go because I feared that in the hospital the authorities would return me to my country,” said Luis.

Luis’ story of hardship is common among the millions of people across the globe who leave their homes, families and everything they know for the hope of a more secure life elsewhere. This migration is a powerful force for shaping society through the spread of ideas, knowledge and even wealth as people and families connect across geographies and cultures.

Migration has also long been a flashpoint for anger and prejudice in every country and context, and these responses can blur the reasons why people relocate their lives and what their arrival means for the places where they settle.

This is where research fills a critical gap. The UC Davis Global Migration Center is a research collaboration across the social sciences, humanities, medicine and law that weaves facts and human experience into the complexity of how we think about migration, both in the U.S. and globally.

“Immigrants are part of the fabric of a country’s economy and society,” said Giovanni Peri, director of the Global Migration Center and a professor of economics at UC Davis. “We want to bring more information, clarity, facts and discussion to shine the light that immigrants are human beings who bring assets with them to their new countries.”

Making the hard choice to leave home

Luis’ story comes from “Humanizing Deportation,” a project that records the stories of vulnerable migrants in Tijuana. The project is led by Robert Irwin, deputy director of the Global Migration Center and a professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at UC Davis. Since 2016, Irwin and his team have collected over 400 stories, each one edited to about five minutes long.

“Migration has become such a politicized issue that either you’re for it or against it,” said Irwin. “We try to get beyond the politics to the details of what's really happening in people’s lives.”

These stories provide a human context for the roughly 3.2 million people U.S. Customs and Border Protection encountered just in 2023 attempting to enter the U.S. without authorization. An estimated 10.5 million unauthorized immigrants currently live in the U.S., representing about 3% of the total population.

Irwin said that what brings so many people to the border is mainly the chance to apply for political asylum. However, to apply for asylum, a person must be on U.S. soil and believe they are in danger of persecution in their home country due to their race, religion, nationality, social group or political opinion.

By these criteria, even a person coming from Haiti, where criminal gangs seek to overthrow the national government, might not qualify. People fleeing poverty, drought or other hardships that make earning a livelihood nearly impossible might also be unlikely to receive a grant of asylum.

According to the immigration data tool TRAC at Syracuse University, people from countries sending the most people had some of the lowest asylum grant rates. People from Mexico had a grant rate of 17.5%. Northern Triangle countries, where it’s been well documented that violence drives migration, also had relatively low rates, with El Salvador at 25%, Guatemala at 23% and Honduras at 22%.

Like many others who head north, Luis ultimately decided to stay in Mexico.

“I have always had in my mind the words of a very wise person who told me, ‘Luis, the American Dream begins where you begin to live,’ and I feel that in Mexico I am doing well and it is where I want to stay, and in the future to be a useful person, to be a productive person, and to help my compatriots that come from Central and South America.”

Global migration, disease and stigma

Migration is, by all measures, a global phenomenon. About 2.3% of the global population, about 184 million people, could be considered migrants for having left the country in which they were born to live in a new nation without citizenship.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 36.4 million of these were war refugees in 2023. Just over half came from three countries: Syrian Arab Republic, Afghanistan and Ukraine.

When large numbers of people end up in refugee camps, migration takes on a serious health dimension. Besides the human toll of disease in these crowded spaces, said Desai, the presence of disease can also attach stigma to a person’s status.

“Communicable diseases already are quite stigmatized, and there's this historical association pinning a communicable disease or an outbreak with immigration,” said Dr. Angel Desai, an infectious disease specialist and assistant professor at UC Davis Health. “In my research with forcibly displaced migration, I try to separate the actual risks from the imagined ones.”

Desai is a physician and treats patients at UC Davis Health in addition to her work conducting research on global public health. She is also a member of the Global Migration Center executive committee.

In a recent study, she and her co-authors looked at outbreaks of Hepatitis E, which is an infection that affects the liver. With roughly a decade of data on outbreaks in refugee camps across a number of African countries, they found that these outbreaks were always associated with crowding, poor sanitation and a lack of infrastructure like running water and sanitary waste disposal systems.

“These outbreaks were not inherent to the population,” said Desai. “Hepatitis E flourishes in situations where you have poor sanitation and a lot of crowding.”

In another study, she and her co-authors analyzed how U.S. news media portrayed tuberculosis (TB) and immigrants. Their analysis showed that the political leanings of news media outlets drove differences in the number of reports they published on the topic.

“Communicable diseases don't care where you're from,” said Desai. “We need to look deeper into the structural and environmental causes of these diseases and really be making sure that our policies help everybody achieve the best health outcomes as opposed to using them as a tool to further stigmatize a group of people.”

Dispelling myths about how immigrants affect crime and jobs

In the U.S., the stigma associated with unauthorized immigration is driven by ideas that immigrants are a threat to people’s safety and to their jobs. Where individual stories offer a granular, personal view into a person’s life, economic analysis applies advanced statistical methods to large datasets to establish facts. This kind of research has found immigrants’ threats to safety and jobs to be a myth.

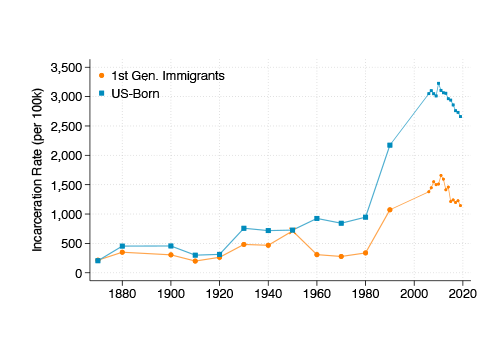

A new study co-authored by Santiago Pérez, an associate professor of economics and Global Migration Center affiliate, analyzed more than 150 years of US Census Bureau data to compare the crime rates of immigrants and the U.S.-born.

The study found that immigrants have had a lower incarceration rate than the U.S.-born in every single year since 1870. Also, since the 1960s the gap in incarceration rates has significantly grown. In recent years that gap has reached 30% overall.

“People often see past migration waves in a more positive light,” said Santiago Pérez, an associate professor of economics and Global Migration Center affiliate. “They think about Europeans who came in the late 19th century and early 20th century and they tend to contrast this with new migrants, but what we find in the paper is actually the opposite.”

Economics research has also shed light on the question of how immigrants affect jobs and wages for everyone. For nearly 30 years, Global Migration Center director Giovanni Peri has published papers on the topic.

For a 2006 report for the American Immigration Council, Peri analyzed over a decade of economic data to understand the dynamics of how immigrant workers shape local job markets. The reality, he found, is much more complicated than a zero-sum-game with a limited number of jobs. That 2006 analysis found that new arrivals were a force for productivity that stimulated investments to generate additional profits.

An April 2024 NBER paper by Peri and co-author Alessandro Caiumi confirm that these findings remain true nearly 20 years later. With improved statistical methods, this new analysis found that immigrant workers at all skill levels either have no effect on jobs and wages for U.S.-born workers or that they generate a slight improvement.

“Instead of a threat to native-born workers, immigrant workers bring with them skills and levels of education that are complementary,” said Peri. “Instead of generating more competition across the board, immigrant workers have almost always increased overall economic opportunity for everyone.”

Changing the law to improve the U.S. immigration system

In the U.S., what ultimately determines who lives here, with or without documentation, is federal law. Legal scholars study how laws can achieve specific goals through the system of laws as a whole.

Kevin Johnson, dean of the UC Davis School of Law and a Global Migration Center affiliate, wrote the book Opening the Floodgates: Why America Needs to Rethink its Borders and Immigration Laws (NYU, 2007), about the potential benefits of a more open-border policy. He said that our current immigration laws, which were passed in 1952 and designed to keep out communists, have long been outdated.

“We once thought communists and immigrants were almost one and the same,” said Johnson. “It’s time for a reconceptualization of immigration law that allows many more people to come into this country.”

Changes to immigration law could help people like Alejandra Juarez, who was deported to Mexico when her daughter Estela was only 8 years old.

Estela and Alejandra’s story is well-known. When Alejandra was first deported, her daughter Estela turned her love of writing into advocacy on her mother’s behalf. Their story was featured at the 2021 Democratic National Convention and was the basis for Estela’s 2022 book “Until Someone Listens,” which was published in both English and Spanish.

Estela was ultimately successful in bringing her mother back to the U.S., at least temporarily. For three years, Alejandra reapplied every year to stay in the country, and every year the family worried her application would be denied. Ultimately, Alejandra decided to return to Mexico, leaving her family behind in the U.S.

“I will continue to fight for an immigration reform until someone listens,” Estela told the Humanizing Deportation team. “I want my story to be a testimony of how using your voice can spark change in the world.”

While broad immigration law reform remains in limbo in the U.S. Congress, Johnson said there are still legal changes that would make significant improvements. One would be to increase the number of immigration court judges to reduce the years-long backlogs on asylum claims. Another would be to offer more visas for low- and medium-skilled workers, such as the roughly 40% of U.S. farmworkers who are immigrants with no legal work authorization.

Johnson cited other quick fixes for people who were brought to the U.S. without authorization when they were still children and have spent their entire lives under threat of deportation to countries they’ve never known.

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program could create a pathway to legal residency and citizenship instead of a two-year renewable deferment in removal. Passing the DREAM Act, still only proposed legislation, would also provide a pathway to legal status for child arrivals.

“Law can be a better tool for regulating immigration and bringing about social justice,” said Johnson.

Labor shortages during pandemic

The U.S. depends on immigrants to support large sectors of the economy, and this became clear during the COVID-19 pandemic. The lockdowns that began in March caused a major change in migration by closing the border and halting applications for asylum. Irwin, who had for years regularly traveled to Tijuana to collect stories, wasn’t able to travel for a year and a half.

Peri and his co-authors did an economic analysis of how the pandemic affected the number of workers available. They found that pandemic-related lockdowns cut U.S. immigration, which in turn left jobs open that were never filled by U.S. residents.

In immigrant-heavy sectors, like construction and agriculture, overall employment dropped by at least 10% in 2020 and barely recovered two years later. In the hospitality industry, employment fell by more than 30% and was still 10% lower in 2022.

Besides an economic contribution, however, Peri said that immigration is central to the fabric of our very society.

“Immigration is the history of who we are in the United States,” said Peri. “Immigration is part of everyone’s family history and the American dream.”