New Book Examines the History of Fathers and Babies

When evolutionary anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy became a grandmother in 2014, she witnessed a phenomenon she never expected to see, one that seemed to run counter to everything she assumed about the division of labor between fathers and mothers. Rather than a protective, if aloof, presence in the baby’s life, David — Hrdy’s son-in-law — was immersed in the nurturing process.

“Watching him, I marveled at the sight of ‘Man the Hunter’ at a bassinet and was suffused with gratitude,” recalls Hrdy, a professor emerita of anthropology. “As my mind traveled back over the infant care I had seen before, I was also struck by its strangeness. This was completely new to me. ‘Wonderful!’ mused the mother and grandmother in me. Then the evolutionary anthropologist in me intervened. ‘How could this be happening?’”

That question was the catalyst that led to Hrdy’s new book Father Time: A Natural History of Men and Babies (Princeton University Press). A comprehensive and wide-ranging work, the book traces Hrdy’s personal investigation into the deep history of male care, beginning with the very first caretakers, male ones among fish over 400 million years ago, through eons of mammalian and primate evolution, and including several thousand years of historical changes across cultures through time leading to this novel 21st century situation.

“Was the paternal care of a newborn really as unusual as my personal history and academic training had led me to assume?” writes Hrdy in the first chapter of the book. “If not, how could male apes possess the potential to respond so tenderly to the needs of a tiny baby? How could men become so selflessly engrossed? Whence this quantum of tenderness?”

Uncovering the quantum of tenderness

According to Hrdy, more men today than ever before in humanity’s known history are caring for babies, really little babies, sometimes right from birth.

In a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services report from 2013, nine out of 10 fathers who lived with children under age five reported that they bathed, diapered, dressed or helped children use the toilet “every day” or “several times a week.” What’s more, between 1965 and 2011, the time fathers spent with their children nearly tripled, rising from 2.5 hours to 7.3 hours.

Just as she was surprised by her son-in-law’s propensity for childcare, Hrdy was surprised by these statistics.

Hrdy proposes that these 21st-century trends in fatherhood aren’t just informed by society’s changing views of masculinity. They are biologically ancient proclivities, ones that have long been present, albeit lying latent, in the brains of modern man. They’re just awaiting activation.

“It takes stimulation in the most ancient limbic recesses of a man’s brain before his full quota of vigilance and commitment gets switched on, screaming ‘This babe before all the world, (I) will keep you safe.’” Hrdy writes. “In researching this book, I set out to learn how 21st-century men could arrive at a place where this happens. But I also needed to understand how men came by the relevant neural circuits and potential in the first place. Chapter by chapter, I struggled to find out.”

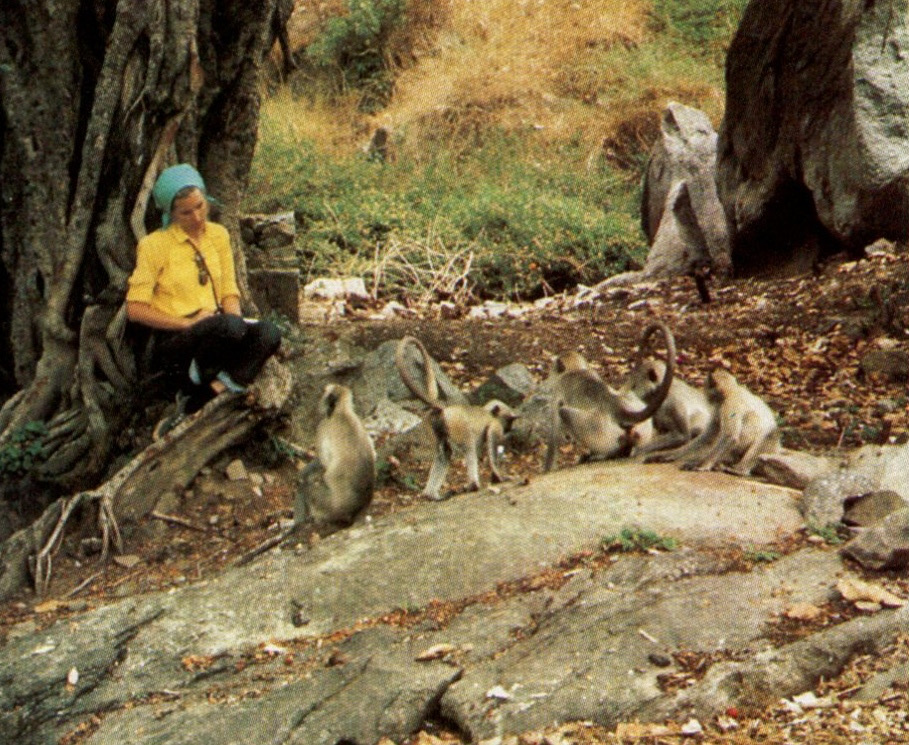

In Father Time, Hrdy aggregates a trove of research about how male brains change when they become fathers. She branches out to humanity’s myriad cultures around the world and examines different species across the animal kingdom, diving into research about paternal care in monkeys, voles, birds and fish, among many others.

What stands out in the human-focused research is how similar men and women are when it comes to changes in brain chemistry prompted by a newborn child.

“Although it’s still not entirely clear what oxytocin does, within six months following birth, baseline levels in new fathers — who had never undergone pregnancy, labor contractions, or milk-ejecting let-down reflexes — were similar to average oxytocin levels in mothers,” Hrdy writes.

Additionally, the areas of the brain known to govern maternal responses — the hypothalamus and the amygdala — are also activated in men who act as primary caretakers.

“These are ‘ancient’ networks dating back to the first mammals, and even further, to their early vertebrate precursors,” Hrdy writes. “They derive from the same highly conserved neural networks that for 200 million years helped hypervigilant mammalian mothers keep their babies safe.”

One ripple is that this ancient response is only seen in men whose primary concern is the safety and well-being of a baby day after day.

“In secondary caregiving men from ‘traditional’ family contexts, neural circuits in the cortical region of their brains, important in social discrimination and decision-making, really lit up,” Hrdy adds. “These neural networks register cues from the baby and the social environment, enabling a caregiver both to cognitively process what the baby is experiencing and also to factor in who else is available to help, so as to organize their responses appropriately and decide what to do.”

Nurturing men’s minds

In her book, Hrdy proposes that the sea-change that occurs in men’s minds when they become fathers is informed by both biology and society. The neural underpinnings are always there, but societal norms dictate and inform how men approach fatherhood. As society’s views on masculinity morph, views that with the late 20th century focus on gender equality have shifted dramatically, there are more opportunities for these ancient neural circuits to be activated and develop.

“Economic considerations, egalitarian ideals, and new definitions of manhood help set the stage,” Hrdy writes. “But biology is at work as well. As men pass their tipping point, neural circuits in the most ancient limbic recesses of their brains are activated. In the course of finding this new source of satisfaction and purpose, these men discover a birthright they had not even been aware of.”

Hrdy notes that to uncover the ancient origins of parental behavior, scientists need to examine the first vertebrates known to care for their young: fish. Of the 28,000 species of fish, about 25% exhibit paternal care, and in most cases, the caretakers are male.

“The molecules and brain circuits implicated in parental care most likely first evolved in males,” Hrdy writes. “If so, the components relevant for tending young stuck around, right there in Mother Nature’s pantry, lying latent pending a use for them.”

Learn more about Father Time: A Natural History of Men and Babies on the Princeton University Press website.