Have you seen the night sky?

That question may seem like one with an obvious answer, but consider this statistic: more than 80 percent of the world’s population lives in areas rife with light pollution.

An artificial phenomenon, light pollution dampens our view of the stars, hindering our connection to the universe above. It’s one of the reasons why astronomical observatories are erected in remote, often pristine, places.

The opportunity to travel to such places drew Lori Lubin to astronomy.

I just loved observing. I loved the community of observers, the experience of being at a telescope, taking the data and looking at the data, working with the support staff, it all just had a great feel to it. You’re in an environment that’s really tranquil and reflective and you go out, look up, and just feel at one with the universe.” — Lubin

While still conducting research today, Lubin, a professor of physics and astronomy, has shifted her focus to administration. As the college’s associate dean for research and graduate studies, she champions research across the college’s disciplines: the arts and humanities, the social sciences, and the physical sciences and mathematics. For Lubin, academic research doesn’t just have the power to change the world for the better. It can help us further understand our place in the cosmos.

“Look at what the intellectual curiosity of humanity has done for us. We’re stuck here on Earth, in a run-of-the-mill solar system, in a run-of-the-mill galaxy, but we’ve looked out into space and figured all this out through technology we’ve created,” she said. “It’s incredible.”

An interest in galaxy clusters

Lubin’s work in observational astronomy has led to her being a world-renowned scientist. Her research focuses on galaxy clusters, some of the largest and most massive objects in the universe.

Galaxy clusters contain hundreds, even thousands, of galaxies. They form in the most overdense regions of the early universe, where over time gravity pulls in more and more dark matter and gas. Because of this origin story, they are enticing cosmological laboratories.

When we look at distant objects, we’re looking back in time and that whole kind of time machine aspect of the universe is really amazing. By observing clusters at different distances from us, we can study how they have evolved with time.” — Lubin

As principal investigator of the Observations of Redshift Evolution in Large Scale Environments (ORELSE) and the Charting Cluster Construction with VUDS and ORELSE (C3VO) Surveys, Lubin has led comprehensive, multi-wavelength studies of distant galaxy clusters, whose light was emitted between five and 12 billion years ago. The work is helping researchers refine models of cluster formation and galaxy evolution.

“Because they’re so massive, the clusters themselves and their evolution are extremely sensitive to the key cosmological parameters of the universe,” Lubin said. “They also trace the large-scale ‘web-like’ structure of the universe and allow us to study large populations of galaxies in extreme environments, far different than that of our Milky Way.”

Mentorship played a key role in Lubin’s trajectory as an academic. Her advice for current students in the field is to explore topics broadly but be specific about who you choose as a mentor.

“When I started out, astrophysics was a very male-dominated field and it still is, but I’ve always had wonderful mentors and for me, I think that’s so important,” she said.

A formative experience

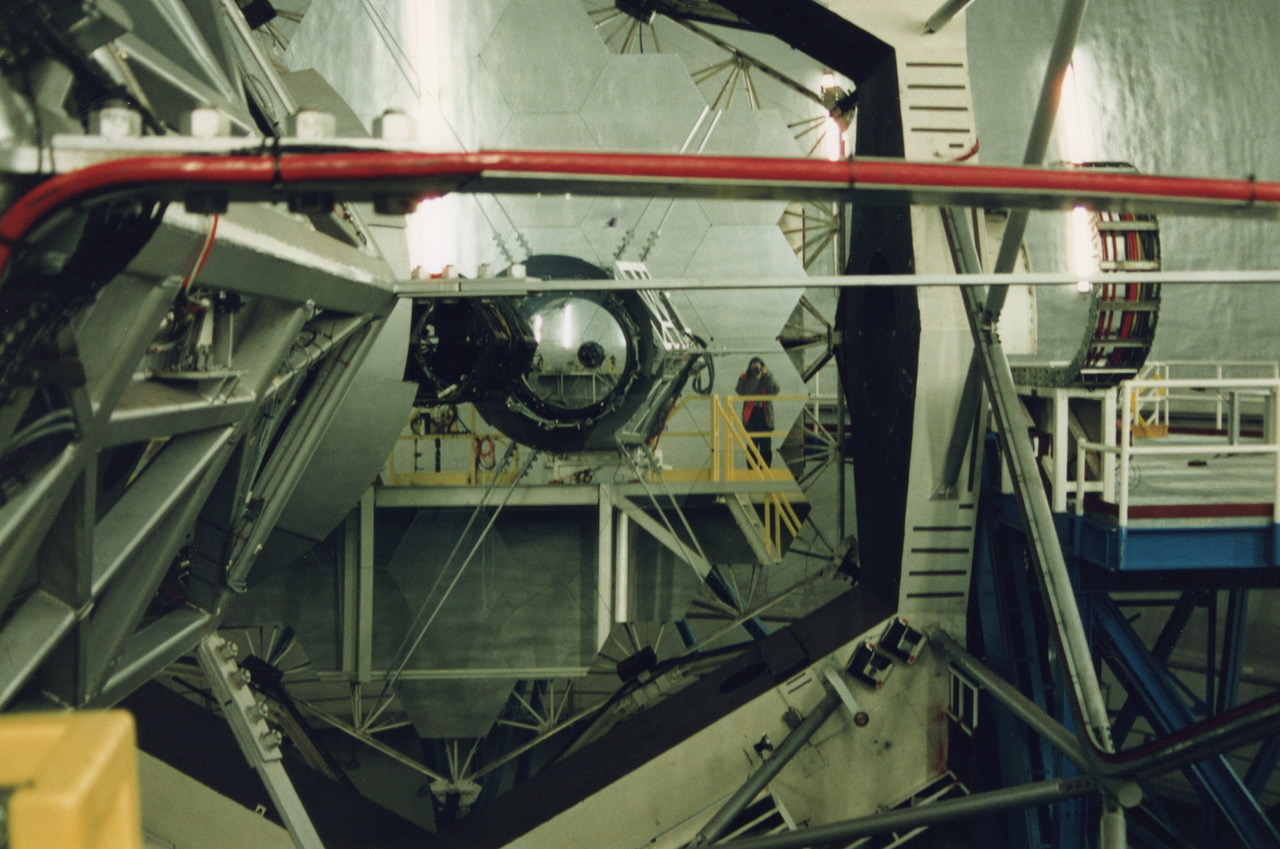

The road to Hawaiʻi’s W. M. Keck Observatory is a winding ascent to the top of Maunakea. The path guides one high above the clouds to a volcanic peak with several astronomical observatories. At roughly 13,600 feet, the mountain’s altitude is so high, the observatories are out of sight for much of the climb. But then, a revelation happens.

“When you’re driving up, you can’t really see the telescopes,” Lubin recalled. “But when they come into view, it’s kind of like this magical experience. It’s just gorgeous.”

Here, above the hustle and bustle of the day-to-day, scientists conduct research at the frontiers of astronomy and astrophysics. Through research and observation, they ponder the nature of the universe and existence. Landmark discoveries made thanks to Maunakea, one of the best sites for astronomy, and the Keck Observatory include finding the earliest known supermassive black hole, the first pictures of an exoplanetary system, and the Nobel-prize winning measurement of the Milky Way's supermassive black hole and the revelation that the universe's expansion is accelerating, among many others.

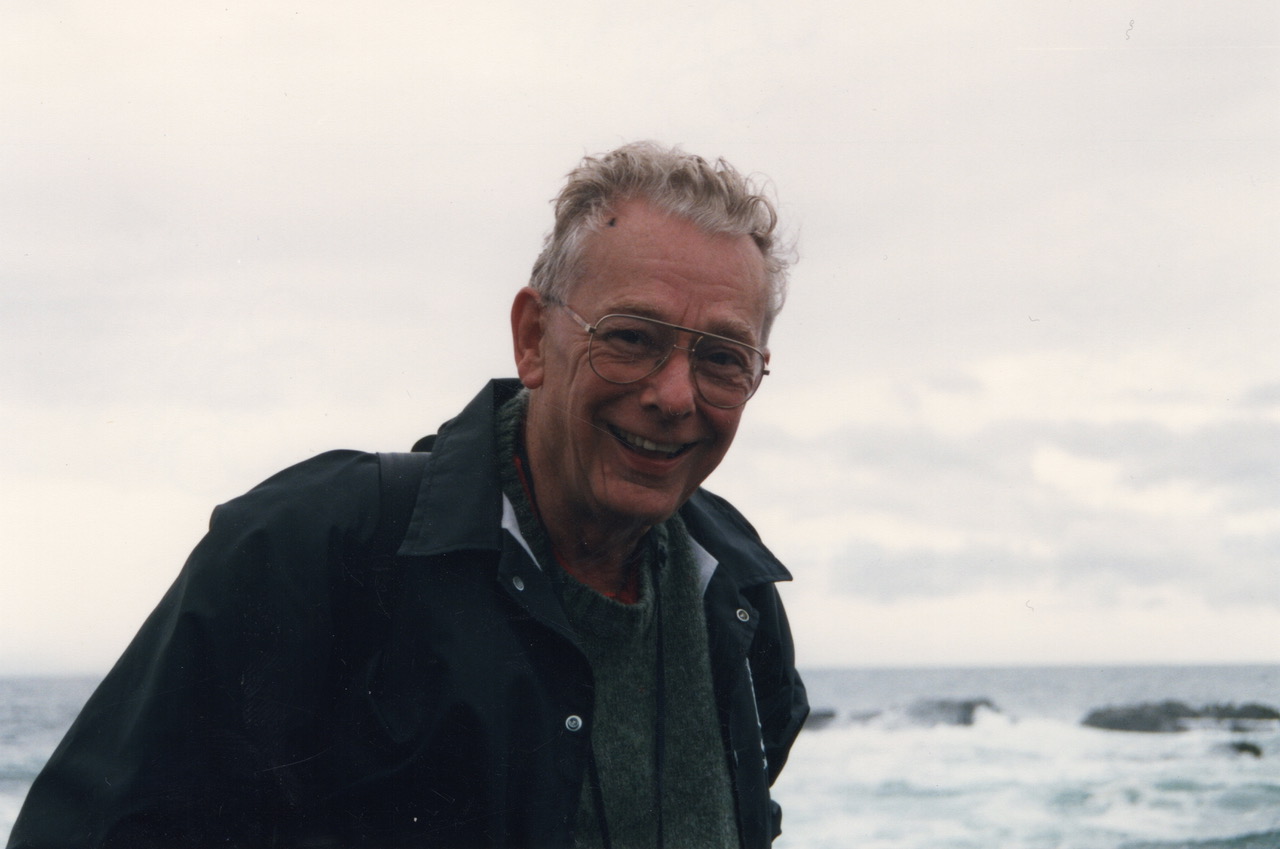

Lubin first made the trek to Maunakea when she was a graduate student at Princeton University. She was there with her mentor, the late renowned astronomer J. Beverley (Bev) Oke, a professor at Caltech.

“He built one of the instruments at Keck and he was just a wonderful man, a wonderful mentor,” Lubin said. “I just loved being with him and talking about science, the workings of the instrument, life.”

Beyond its strong scientific value, Maunakea is environmentally important as well as a culturally significant and sacred site for Native Hawaiians. Over the years, there have been disagreements regarding how the site has been managed.

In 2022, the state passed a new law shifting the governance of Maunakea from the University of Hawaiʻi to the Mauna Kea Stewardship and Oversight Authority, a “group of stewards comprising Native Hawaiians, cultural practitioners, and representatives of the state and other institutions,” according to Scientific American. “It’s a shift many hope will pave a path through an anguished, long-simmering impasse that in the past few years has intensified and polarized astronomers and Native Hawaiians as never before.”

As officials continue to address issues surrounding Maunakea’s management and work towards a community astronomy model based on mutual stewardship of the mountain, Lubin is thankful for the many nights she spent at the revered site.

I am very grateful for the gifts that this great mountain has given me." — Lubin

A pivot to administration

In 2021, after nearly 35 years of research, Lubin pivoted to academic administration, taking on the role of associate dean for research and graduate studies at the College of Letters and Science at UC Davis.

Research of all sorts is interesting. Like I love my own, but the beauty of this job is I get to learn about all this incredible research across the college. It’s the perfect job for me because I really enjoy learning about other things. I really enjoy interacting with people who are experts in what they do.” — Lubin

Recently, Lubin spearheaded the organization of the college’s first Research and Creative Activities Celebration. The event showcased the breadth of academic activities occurring across the College of Letters and Science and its affiliated centers, with faculty presentations and panel discussions.

Lubin’s goal is to provide faculty and graduate students with opportunities to engage with and further their research, whether through financial support, encouraging interdisciplinary collaborations or providing a space for networking.