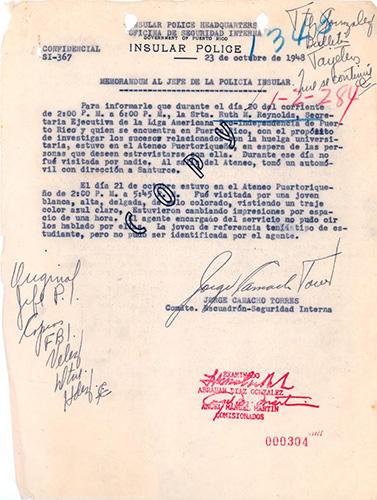

The gag order was used to criminalize public demonstrations of support for independence. State surveillance expanded. Neighbors reported on neighbors. Anyone even associated with the independence movement risked losing their friends and their livelihoods.

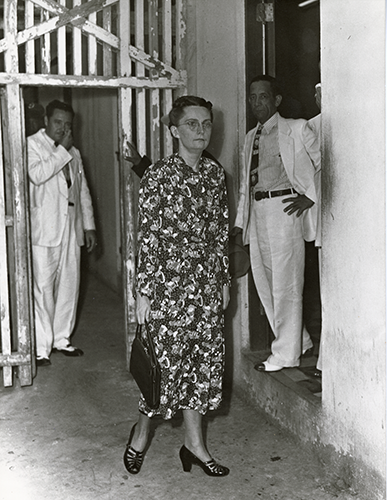

“This is the Puerto Rico that Ruth Reynolds had thrown herself into,” said Lisa Materson, a professor of history in the College of Letters and Science at UC Davis.

Materson’s new book, Radical Solidarity: Ruth Reynolds, Political Allyship, and the Battle for Puerto Rico's Independence (UNC Press, 2024), tells the story of an unlikely activist and radical pacifist from South Dakota who followed her conscience to Puerto Rico in the 1940s and remained steadfast in her support even when members of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico took up arms in fighting for independence.

“This was a very interesting as a kind of puzzle to think about” said Materson. “How did people with such profound different life experiences and political ideologies find common cause?”

A fascinating story never fully told

Puerto Rico is a U.S. territory in the Caribbean about 1,000 miles from Florida. The U.S. government has controlled Puerto Rico since it invaded the archipelago in 1898. Since 1917 every Puerto Rican has also had U.S. citizenship. After World War II, the archipelago was one of a handful of remaining U.S. colonies, and the site of expanding U.S. military operations.

In 1952, the U.S. created the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, which gave Puerto Ricans more local autonomy on some matters but not that of full statehood. For many Puerto Ricans who sought full independence, this relationship amounted to permanent colonial domination.

Materson initially set out to write a book about Puerto Rican women in the independence movement before and after 1952. During interviews with these independentistas in Puerto Rico between 2010 and 2012, several mentioned how important Reynolds was to the struggle.

Then, while combing through the Center for Puerto Rican Studies (CENTRO) Library and Archives at Hunter College in New York, Materson met fellow historian Olga Jiménez de Wagenheim, who was also researching women independentistas. It was Jiménez de Wagenheim who suggested Materson write a book about Reynolds.

Reynolds had long been considered a significant figure in Puerto Rico’s independence movement and CENTRO holds a large collection of her papers. Yet, her fascinating story had never been fully told.

Applying pacifism to an independence movement

Ruth Reynolds was born and raised in South Dakota and went to school in the Midwest where she became a political pacifist. She then moved to New York in 1941 to learn about Gandhian non-violence and radical pacifist organizing in Harlem at a time of growing activism seeking equality for African Americans. New York was also home to a large Puerto Rican population, some of whom had been imprisoned for their political activities along with draft resisters and activists.

It was on the U.S. East Coast that Reynolds encountered key figures in the struggle for Puerto Rico’s future. On one side was Pedro Albizu Campos, a graduate of Harvard Law School and a veteran of the U.S. military, who was also in New York in the early 1940s. Since 1930, he had led the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico which demanded U.S. withdrawal from the archipelago and unconditional independence as the key to Puerto Rico’s future.

On the other side was Luis Muñoz Marín, then Puerto Rico Senate President, whom Reynolds met in D.C. in 1945. Muñoz Marín maintained that the territory’s development and prosperity required a free-associated state, or commonwealth, status with the U.S.

It was Albizu Campos, however, who inspired Reynolds to devote her life to the cause of Puerto Rico’s independence. In 1944, she helped found the American League for Puerto Rico’s Independence. In 1945, she argued for independence to the U.S. Congress and then traveled to Puerto Rico for the first time to learn more.

A political pacifist encounters U.S. colonialism first-hand

Reynolds was a self-taught investigator and interviewer, and in Puerto Rico for the first time in 1945, she traveled across the territory to ask Puerto Ricans what they wanted for their nation. Through a network she began to build in New York, she soon had access to people in powerful positions in and out of government. Within several months, Reynolds had a nuanced perspective of figures and organizations across Puerto Rico and of the growing tensions over Puerto Rico’s future status.

She returned to Puerto Rico in 1948 to document the violent government crackdown on pro-independence strikers at the University of Puerto Rico. The violence soon expanded. In response to the student strike, the government passed the gag law, which made it a crime to advocate the overthrow of the insular government.

“In practice,” said Materson, “the gag law was used against anyone who publicly advocated independence, not just supporters of the Nationalist Party.”

In 1950, Albizu Campos would call for an uprising to declare an independent Puerto Rico. The government response was immediate. Luis Muñoz Marín, now governor and a strong advocate for a continued association with the United States as a commonwealth, declared martial law. The U.S. and Puerto Rico Air National Guard dropped 500-lb bombs on Jayuya and attacked Utuado, both independentista strongholds.

By this time, Reynolds was writing a book based on her interviews and research in spite of constant government surveillance. Everything came to a halt when she was arrested.

Reynolds was sentenced to prison for conspiring to overthrow the government of Puerto Rico, though she had no part in the Nationalist Party uprising. By then, the FBI and Puerto Rican authorities had compiled a comprehensive surveillance file on her. She would spend 19 months alongside other women political prisoners.

“She was willing to give up her own freedom, just as those with whom she claimed solidarity did,” said Materson.

By the time of Reynolds’s release from prison in 1952, the commonwealth had been inaugurated.

Finding radical solidarity

Throughout her involvement with the movement that would endure for the rest of her life, Reynolds remained a pacifist as well as an ally to the Nationalist Party and later to New Left youth movements.

Elaborating upon Reynolds’s political practice as “radical solidarity,” Materson named three key components:

- Rather than focus on the differences she had with her nationalist allies, Reynolds focused on what they had in common: a shared critique of U.S. colonial state violence and militarism.

- Reynolds believed that North American allies like herself could choose their tools against U.S. colonialism but should not tell Puerto Ricans how to conduct their own struggle for sovereignty or how to run an independent Puerto Rico.

- Her advocacy for Puerto Rican independence came from and leveraged her identity as an American citizen.

Materson found that through her activism, Reynolds was fulfilling her own liberation and the promise of the ideals of American democracy. After she was released from prison she would spend the rest of her life calling attention to U.S. state violence in Puerto Rico, the original 1898 invasion to conscription, the construction of military bases and the use of policing powers to silence opponents.

“Reynolds equated patriotism to the United States with advancing an anti-colonial agenda,” said Materson. “She said, I'm working for Puerto Rico’s independence because I want the U.S. to live up to its ideals, and for the U.S. to live up to its ideals, it can't hold another nation in bondage.”

Meeting allies who loved Reynolds

In her lifetime, Reynolds collected contemporary newspapers and pamphlets. She kept decades of private correspondence. She also interviewed hundreds of people involved in the independence movement. Toward the end of her life, Reynolds herself sat for hundreds of hours of interviews.

Puerto Rican scholar-activists at CENTRO knew the value of recording Reynolds’ story and all that she had collected for that period in Puerto Rico’s history. They gathered the material together in an important collection that was critical to Materson’s research.

At the same time, an archive doesn’t tell the whole story.

It had been Isabel Rosado, one of the independentistas, whom Materson interviewed at the earliest stages her research in the 2010s, who not only shared Reynolds’s importance in the struggle, but also the deep friendships that nurtured her solidarity activism. Rosado was imprisoned for over 11 years. In that time, she spent 19 months with Reynolds.

In 2010, Materson drove to Ceiba, Puerto Rico with Emilia Rodríguez Sotero, an independentista whose story Materson has written and published. Rosado lived in an assisted living home, and when they arrived was helped into the room. An aid cut up the papaya Materson had picked up on the way as they began to talk.

Rosado was 102 years old at the time. She would pass away in 2015 at the age of 107.

“Rosado was sharp and as committed as ever to an independent Puerto Rico,” said Materson. “She talked in these loving terms about Ruth Reynolds.”

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE THESE STORIES

Fighting for a Fulfilling Life

As historian Traci Parker writes a new biography, she is learning just how much Coretta Scott King contributed to her husband’s ideas and actions, and how his story is also very much her own.

Connecting India’s Hindu Past and Present with the Ganges River During the Kumbh Mela

The Kumbh Mela pulls together multiple strands of India’s deep cultural past with its status today as the second-most populous nation in the world with international influence and ambition to reach for the stars. Over 400 million are expected across the duration of this year’s festival, which runs from January 13 through February 26, 2025.