A Ph.D. Student and Military Veteran Maps Brain Connections Involved in Anxiety

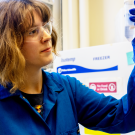

Zachary Oakland looked through the microscope for glowing brain fibers in cells he had injected with dye that turns fluorescent under blue light.

In his first year at UC Davis as a Ph.D. student in psychology, this work is very different from the research he did as an undergraduate at Sacramento State. It’s a world away from his office at the U.S. air base in Jordan where he interviewed with faculty remotely while applying to graduate school.

Oakland’s path from enlisting in the U.S. Air Force right out of high school to pursuing a Ph.D. at UC Davis is an uncommon one. He is also starting to understand the unique challenges of being a graduate student whose path doesn’t mirror the paths of his peers. What drives him, he said, is a need to understand post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a debilitating condition that many veterans bring home.

“I've seen first-hand some of these different things that affect veterans, and I just want to do my due diligence as someone who is curious about the brain,” said Oakland.

From military service to exploring fear in the brain

Anxiety has always been a part of Oakland’s life. He always enjoyed learning, but by the time he reached high school he could barely manage being around other people. Instead of pursuing college, he followed in his parents’ footsteps and join the military. He chose to enlist in the Air Force.

“In my head now, it doesn't make sense,” he said. “The military was probably the worst thing I could have done. I’m getting screamed at every day. It’s just crazy.”

The experience was a kind of exposure therapy, he said. In basic training he bunked with 50 other men. There wasn’t a moment where he didn’t have to be around someone. Even so, he stayed after his first five-year term of active duty ended, and in 2019 he joined the Air National Guard for another four years. In that time, he served in Iraq, Kenya, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan and Kuwait.

While in the Air National Guard, he enrolled at Sacramento State and began taking classes in psychology. Studying the brain’s amygdala, a region that is important for anxiety, became a way to understand his own experiences of anxiety.

He found a position as a research assistant in Professor Sharon Furtak’s psychology lab where he helped to test a way to blunt fear responses in rodents. He took part in the McNair Scholars program on Furtak’s recommendation. He also began to develop his own ideas and presenting his research at conferences.

“From there I was just like, I want to do this full-time,” said Oakland.

Building a path to graduate school from abroad

Oakland’s final deployment was to Jordan in 2023 as the non-commissioned officer in charge of load planning at the Air Terminal Operations Center. It was there he finished his Ph.D. applications, and remote interviews started a week after a drone attack that killed three soldiers in their sleep at a nearby Army base.

When Oakland got online for those interviews, his base was on high alert. The Wi-Fi was spotty. Everyone was geared up. They were conducting bunker drills to prepare for bomb attacks. He did his interviews in uniform.

“I was intrigued by his background,” said Trainor. “I've found that people who did something very different before going back to school treat it really seriously.”

Trainor said that what impressed him most about Oakland wasn’t just his perfect undergraduate GPA or the effusive praise from his professor at Sacramento State. It was that when they first met in person, Oakland had already read and understood many of Trainor’s published research papers.

“He could talk about them,” said Trainor. “He understood them at a level that experienced graduate students could. I've never experienced that in an interview.”

Oakland was accepted to Ph.D. programs at UCLA and UC Davis. He chose UC Davis because of the research here.

Leaning into resilience in student life

Right now, Oakland is helping to identify the circuitry in the brain involved in different types of social anxiety. The research is done with mice because mice and humans share many of the same brain regions and brain function.

Oakland only joined the lab nine months ago and is already working on projects of his own. What he sees under the microscope could mean a new understanding of oxytocin, a neurotransmitter commonly thought of as the love hormone. Oakland came up with an idea of how different brain regions using oxytocin might interact with each other, and he is testing that idea now.

“It's an amazing idea,” said Trainor, whose research is funded by the National Institutes of Health. “If he’s right, it could explain a big gap in our lab’s story. We know oxytocin has opposing effects on behavior acting in different parts of the brain, but we don’t know if they interact with each other.”

Looking through the microscope lens, Oakland could see brighter spots of green fluorescence that might be the brain cell fibers he’s looking for. By now he knows the different parts of the brain and what they do. He knows theoretically how different regions of the brain communicate with each other and he knows he collected the brain material correctly before he put it on the plate.

“I can see the fluorescence there, and I can see what look like axonal fibers,” he said.

Learning this new process is one of a many new challenges he’s finding as a Ph.D. student. In a matter of months, he traded his military uniform permanently for a white lab coat, protective googles and purple rubber gloves. He said that his past achievements in the military give him confidence that he will succeed.

“Everybody's got their own path, but you as military veterans are resilient,” he said. “It doesn't matter your age. You were able to do all these amazing things at 18 when you first joined. For me, if I was able to tolerate more than 10 years of really stressful experiences. I could easily push forward here.”

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE THESE STORIES

New Research Suggests Why Males and Females Respond Differently to Social Stress

A team of psychologists in the College of Letters and Science has found that testosterone is the key hormone that drives gender-based differences in responses to social stress. The study encompassed six separate experiments with mice to isolate what changes in the brain drive these differences between males and females.

The Roots of Fear: Understanding the Amygdala

Scientists at UC Davis have identified new clusters of cells with differing patterns of gene expression in the amygdala of humans and non-human primates. The work could lead to more targeted treatments for disorders such as anxiety that affect tens of millions of people.