Psychologist Steven Luck Receives Highest UC Davis Honor for Teaching and Scholarship

In psychology research, attention describes when our brains focus on something specific to the exclusion of everything else. When focus on a tree, a bird, or the face of the person in front of us, this attention determines where the brain devotes its energy.

What we focus on is a choice.

Across his career, Distinguished Professor of Psychology Steven Luck has shifted his own focus multiple times, from mainly research to an intense focus on teaching and mentoring students who make the most out of every opportunity. For this work, Luck has just received the 2025 UC Davis Prize for Undergraduate Teaching and Scholarly Achievement.

“Professor Luck’s teaching and research are truly exemplary, yet it is their interconnectedness that distinguishes him as a teacher and scholar,” said Estella Atekwana, dean of the College of Letters and Science. “Professor Luck is a truly exceptional scholar who is dedicated to bringing his expertise and his commitment to the creation of knowledge to our students.”

A mentor paves a path to research

When Luck first enrolled as an undergraduate at Reed College in Oregon, he decided to major in psychology knowing nothing about the subject.

“I really knew less than nothing, because the things that I thought I knew were wrong,” said Luck.

In his first psychology course, Professor Allen Neuringer, gave a lecture that compared animal learning and behavior to the way humans make decisions based on what’s been reinforced in our lives.

For Luck, the concepts in that first lecture were completely unexpected. The professor himself was inspiring.

“He was a really wonderful role model in terms of combining teaching and research. I was sort of imprinted on that right from the start of my first year of college.” — Luck

At the start of Luck’s second year, Neuringer hired him as a research assistant. Neuringer was inspiring as a teacher but was also a very serious researcher in his field. The work Luck did in Neuringer’s lab turned into his first peer-reviewed publication. This early research experience paved Luck’s way to graduate school and then to his first faculty appointment at the University of Iowa.

Connecting what we see to what we remember

For his first 12 years as a professor at the University of Iowa, Luck taught classes but focused mostly on the research that would make him a pioneer and leader in cognitive neuroscience. Today, he is a leading authority on event-related potential, or ERP, a technique used to study shifts in the brain’s electrical field in response to something we sense, think or feel.

Luck measures ERPs with electroencephalography, or EEG, which uses a cap of sensors worn over the scalp to pick up electrical signals in the brain. These signals show what someone is focused on at any given moment, and that focus affects what we remember.

Luck’s research has shown that attention operates through many different systems in the brain, from systems that perceive everything around us to how we make decisions. With colleagues at the University of Maryland, he has also shown that schizophrenia, which is characterized by a state of constant distraction and a lack of focus, may actually be an incredibly strong focus on the wrong things.

In 2006, Luck published a book that was the first comprehensive guide on conducting ERP experiments in cognitive neuroscience and related fields. He began holding ERP workshops that trained other scientists on the technique. For the last 15 years, a grant from the National Institutes of Health has provided full scholarships to those workshops for students, postdocs and professors from around the world.

“I didn't really realize until I had been doing these workshops for a few years that this is teaching,” said Luck. “It wasn’t just my scholarship that I loved. It was teaching the world about it.”

Students who inspired teaching

When Luck arrived at UC Davis in 2006, he noticed right away that the students were different from those he taught in Iowa. UC Davis students were more diverse, and for many an education here would have a bigger impact in their lives.

“The students here seemed to understand that they had a rare opportunity to be at a place like UC Davis and they were going to make the most of it.” — Luck.

Luck began to think more deeply about how he taught his undergraduate courses. Psychology is the largest major at UC Davis by enrollment. Introductory psychology courses are taken by hundreds of students at a time. Luck quickly realized that lecturing isn’t the best way to teach the ideas and concepts that are most important.

He decided to rebuild the courses from scratch. With a small amount of funding and a course on online and hybrid learning with the Center for Educational Effectiveness, he set to work recording video lectures and creating online activities for students to access outside of class time. This shift in focus made it possible to have deeper conversations about the material in small-group, in-person discussion sections.

“In my own classroom I use so much of what I've learned from these colleagues about what really works, and not what works in general but what works with the students at UC Davis,” said Luck.

Becoming a mentor for student researchers

Luck saw that his focus on teaching was having a positive impact, and the difference was even more pronounced among students he mentored in his lab. However, the number of students he could work with was limited.

“He wanted to have an even bigger impact beyond what he was able to do in his own lab,” wrote Emily Kappenman, an associate professor of psychology at San Diego State University. Kappenman first worked with Luck at UC Davis as a graduate student and then as a postdoctoral scholar and assistant project scientist.

Like Luck, she had taken part in research early on as an undergraduate at Indiana University, Bloomington. However, most undergraduate research assistants Luck was hiring had only applied for the position in their third and fourth years.

“By their third or fourth year, they didn't have enough time to do really significant research by the time they left whereas we had both had the experience of having spent many years doing research as undergrads,” said Luck.

In 2014, Luck and Kappenman founded Accelerating Success by Providing Intensive Research Experience, or ASPIRE, which Kappenman co-directed with Luck for its first two years. With ASPIRE, first- and second-year students immediately begin conducting research under the direct supervision of a UC Davis faculty mentor who sees them through to graduation. Today, more than 50 faculty are part of the program campus-wide.

“He gave me an incredible amount of independence, to a level frankly unheard of at the undergraduate level,” wrote Raphael Geddert, a Ph.D. candidate in psychology at Duke University who Luck mentored through ASPIRE. “I singlehandedly designed and programmed an experiment for an EEG study, collected the data myself, and analyzed and wrote up the results into an initial manuscript that would eventually be published.”

Advancing students who make the most of opportunities

About five years ago, Luck started to think differently about the ASPIRE program. Up to that point, the focus of the program had been on students who the management team thought would achieve the most.

“I started worrying that taking students who had already had all of the advantages and giving them even more opportunities was just perpetuating inequity.” — Luck.

The ASPIRE team decided to shift their focus to students who were going to make the most of the opportunity, whatever their background. While some students might bring research experience from high school, others might have volunteered in their community or worked at Walmart and reached assistant manager by the time they graduated.

Today, over half of the UC Davis students who take part in ASPIRE are either first-generation college students or come from historically underrepresented groups or low-income backgrounds. All of them receive the kind of early mentorship and research experience that shaped Luck’s own trajectory.

“Many of our students who come from very challenging backgrounds have really thrived,” said Luck. “Some of them are now in Ph.D. programs at other top universities.”

Attention to the future of teaching

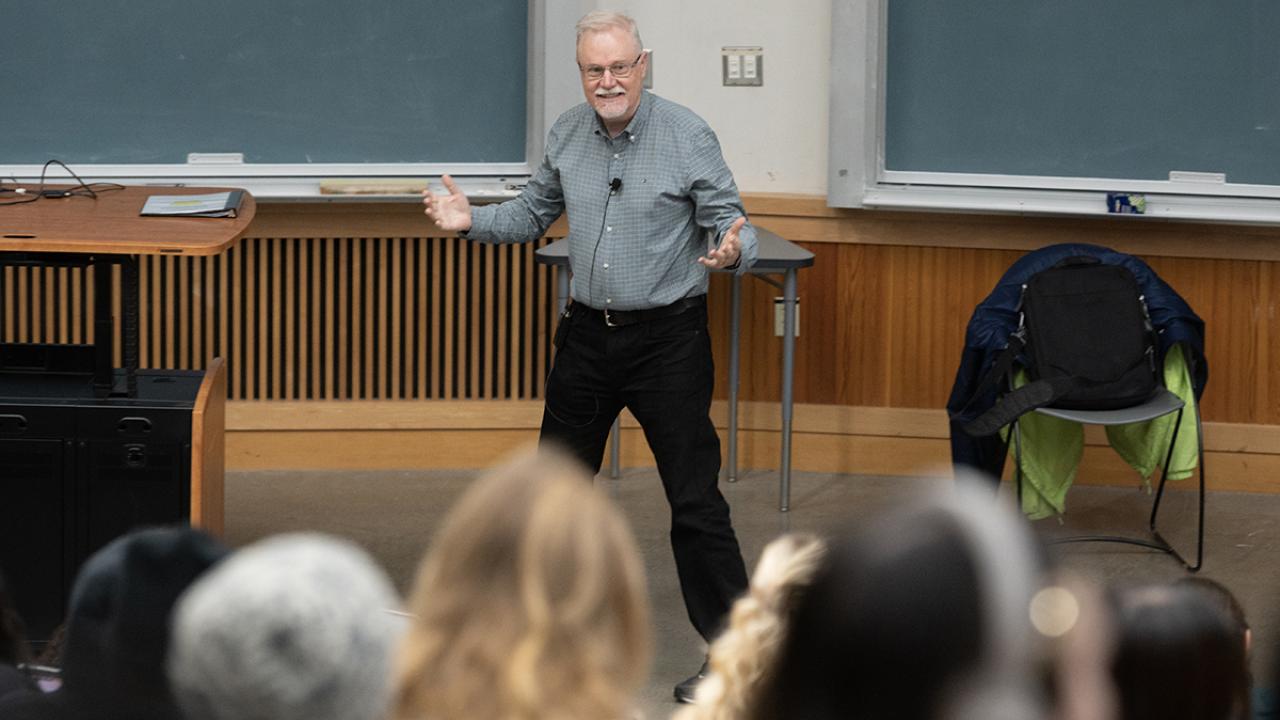

This fall, Luck is teaching PSC 1Y: General Psychology to 800 mostly first-year students. It follows the innovative hybrid model he continues to improve. On December 6, his lecture began with an overview on mental health in teenagers and young adults, a topic that was timely given final exams and the coming holiday break.

Luck’s lecture was interrupted by Chancellor Gary S. May appearing on the big screen overhead behind him with a message to students that their professor had been awarded this year’s Prize for Undergraduate Teaching and Scholarly Achievement. After remarks from Provost Mary Croughan and academic leadership from across campus, Chancellor May joined the celebration in person to help hand out bags of popcorn.

The surprise was fitting. The course is a lot like the one where he first sat down knowing less than nothing and, with the right teacher, quickly realized what Luck wanted his future to be. In this sense, he has always followed in the footsteps of his first mentor Allen Neuringer, who remains a close friend today.

“Our students are not normal human beings,” said Luck. “They are just exceptional and interesting. They often come from very disadvantaged backgrounds but they are willing to work really hard. Thinking about our students is a big part of what I do.”

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE THESE STORIES

Program Gives Jumpstart to Student Researchers

A program that gets students into labs as early as their first year at UC Davis transforms lives — leading many to pursue careers in research. Accelerating Success by Providing Intensive Research Experience, or ASPIRE, has begun reaching out to a wider pool of students.

UC Davis Receives $2.5 Million Research Grant to Study How Diabetes Affects Children’s Cognition

New research led from UC Davis is part of a national consortium studying connections between Type 1 diabetes and cognitive decline in children. With a $2.5 million grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, this study builds on research on diabetic ketoacidosis in children.