We live in a geometric world. From the rectangular skylines of our cities and the orbiting planets of our solar system to the symmetry of butterfly wings and the spiraling double helix of DNA, every shape has its place.

For as long as he can remember, Ryosuke Motani has been fascinated by shapes. And he’s built an illustrious paleobiology career studying them.

“When you see shapes like that, it’s one thing to say, ‘Wow,’” said Motani, pointing to the long-beaked pterosaur skull in his office. “But then, you want to think about what that shape means, and when I say ‘what that shape means,’ I mean, what does it do in the world? Why is that shape there under these circumstances?”

For decades, Motani, a professor in the UC Davis Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, has teased apart that very question by studying fossils in tandem with leading-edge computational and chemical analysis techniques. His research has led to landmark discoveries, from using eye socket measurements to determine that some dinosaurs were nocturnal to revealing how land animals adapted to the ocean, among a host of other discoveries.

For his contributions to the field, Motani was recently named a 2024-2025 Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar. As part of the appointment, Motani will deliver public lectures and lead classroom seminars at various colleges and universities across the country.

“I feel very fulfilled because this was unsolicited,” said Motani, who had no idea about his nomination. “I’m always looking at myself in a supporting role, so to have someone see value in my work, I thought, was very remarkable. I was very thankful.”

The honor is one among many for Motani, who in 2022 was elected as a fellow of the California Academy of Sciences, an honor reserved for distinguished scientists making outstanding contributions to the natural sciences.

Motani’s path to distinguished scholarship was forged by a confluence of both personal interest and happenstance. And it all started with an extinct marine reptile known as ichthyosaur.

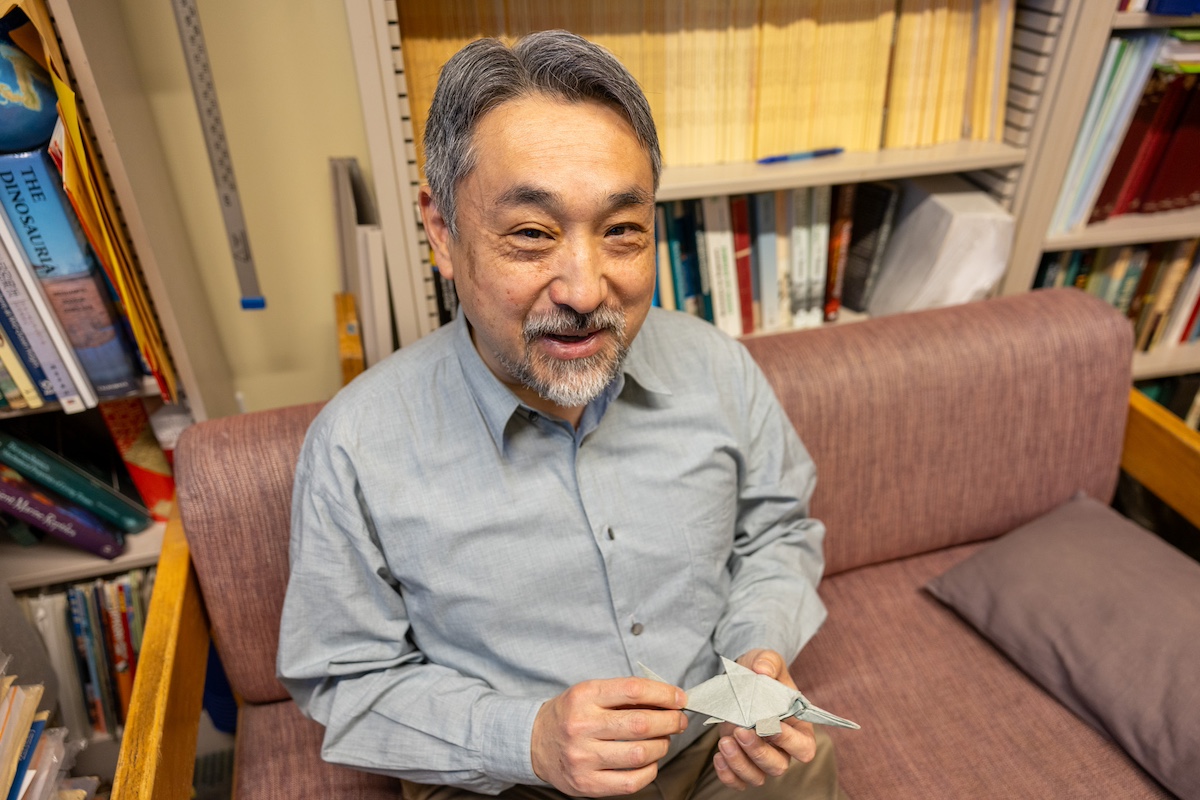

Motani poses with an origami ichthyosaur. (Greg Watry/UC Davis)

Finding vertebrates

When Motani was an undergraduate paleontology student at the University of Tokyo, he didn’t have many options when it came to specific organisms to study. Motani was interested in vertebrates, but the university’s department specialized in invertebrates. When Motani notified his senior thesis advisor of his interest, he learned there was only one domestic reptilian fossil in the university’s possession. That fossil belonged to an ichthyosaur, a creature that Motani didn’t initially have an affinity for.

“In my dinosaur picture books, they always had a page dedicated to ichthyosaurs and I always thought, ‘Why don’t they have just another page for dinosaurs? Don’t waste the page,’” he added with a laugh. “That’s what I used to think as a kid.”

An artist rendition of the ichthyosaur Ophthalmosaurus icenicus. (Wikipedia)

Despite the initial lack of interest, Motani quickly fell in love with the ancient beast. So much so that he continued studying its evolution while pursuing a doctoral degree at the University of Toronto. Eventually, he developed a specialty in morphology — studying the shape of animals to learn about the physical constraints behind their evolution.

Part of that research includes an interest in convergent evolution, which is when animals develop similar features despite not being closely related. Thanks to Motani’s research, we’ve learned that ichthyosaurs initially looked like lizards with flippers but eventually became fish-shaped, just like whales did some 200 million years later.

Five steps to the sea

Nearly 10 years ago, Motani and an international team of researchers discovered a fossil in China’s Anhui Province from an amphibious ichthyosaur. Dated to about 248 million years ago, the fossil, measuring 1.5 feet long, was the first of its kind and filled a gap in the ichthyosaur fossil record, linking the marine reptile to its terrestrial ancestors. The research was published in the journal Nature.

With a shorter snout than its marine counterpart, the amphibious ichthyosaur showed more similarities to land reptiles existing at the time. What’s more, its flippers “may well have allowed limited terrestrial locomotion given their unusually large size … enabling seal-like flipper bending on land,” Motani and his co-authors wrote in the paper.

Pixabay.com

Further exploring this research thread of land-to-sea transitions, Motani and his UC Davis colleague Distinguished Professor Geerat Vermeij, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, published a paper in Paleobiology that chronicled 69 instances of land animals attempting to transition to marine environment over the last 250 million years.

“When land vertebrates colonize the sea for living, like it happened in whales, they have to clear many hurdles, such as holding the breath and making friends with salt,” Motani said. “They usually do this in five steps. Many groups fell short of going through all five but some remarkable ones, such as ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs and mosasaurs, completed the steps and prospered.”

The successes and failures of these land-to-sea transitions will be one of Motani’s lecture topics as a Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar.

“I really look forward to meeting all those students and the public who are interested in science,” Motani said. “Some of the discussion topics I suggested, such as mass extinction, could be controversial and I look forward to hearing different opinions. We can collectively learn from each other and enrich our lives.”

As as a 2024-2025 Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar, Motani will deliver public lectures and lead classroom seminars at various colleges and universities across the country. (Greg Watry/UC Davis)